Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

A new report from Omdia highlights the reasons why development costs are skyrocketing.

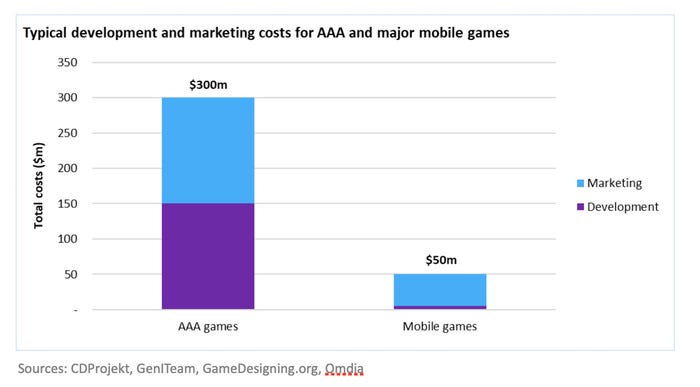

It cost $174m to make Cyberpunk 2077. Normally development budgets are tightly guarded secrets, but in this case we know because CD Projekt Red published the total cost of the project in an official post-mortem following the game’s disastrous launch in 2020. Cyberpunk’s development was troubled by everything from unrealistic hype to overwork of development staff, but one thing that didn’t attract much attention was the huge cost of the project. Development budgets of upwards of $150m have become unremarkable for modern AAA games—and this actually greatly understates the total cost, which can easily reach twice that number once marketing is taken into account.

As recently as a decade ago, only a handful of extravagantly expensive titles had ever cost more than $50m to make. But the last two console generations have seen an acceleration of development costs which is now reaching a point that calls into question the sustainability of AAA games development. Mobile games, meanwhile, face a parallel challenge. While developing for less powerful mobile devices is cheaper, the cost of user acquisition is rising prodigiously and can often be as much as ten times the core development budget—threatening a similarly unsustainable cost spiral.

The core driver of cost increases is fundamental: diminishing returns on improvements in graphics hardware. Every subjective step up in graphics quality requires a greater increase in raw rendering power than the last. But while manufacturers have done an impressive job of maintaining an exponential rate of improvement in raw hardware performance, human effort does not scale so easily. Vastly bigger and more detailed games are now possible, but require far more work to create. This process is now approaching a tipping point where costs have begun to accelerate alarmingly.

In theory, it should be possible to simply stop chasing ever shinier graphics and bigger worlds, but the dynamics of the console market make it extremely difficult to break out of the graphical arms race. Publishers must pay the platform holders 30% of their sales, but Sony and Microsoft themselves are not just exempt from this tax, but subsidized by it, giving them far greater financial wiggle room. Moreover, developing impressive graphical showcases helps to sell their consoles, which in turn generates further revenue, fueling a virtuous cycle. Third-party publishers, on the other hand, do not benefit from any such positive feedback loop, but still cannot afford for their games to look dated compared to first-party output which sets the standard in the eyes of consumers.

Mobile challenges

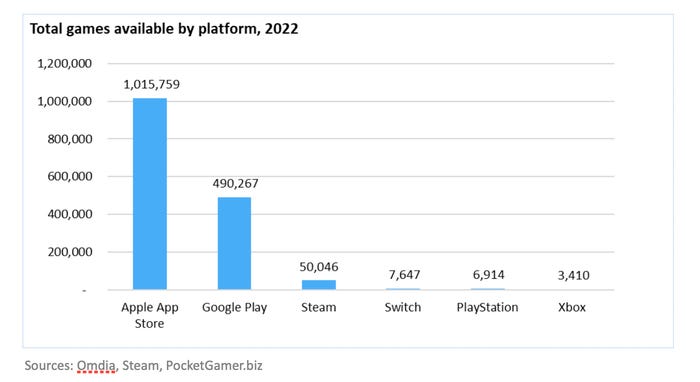

These exact dynamics do not apply to the same extent in the mobile games market where graphics aren’t as much of a selling point. But the economics of mobile game development are also troublesome. The potential return on investment is much higher in mobile, which benefits from lower core development costs and a bigger target market. But the chances of success for any individual game are much lower. When you consider that there are a million games on the Apple App Store, compared to just over 50,000 on Steam, and a few thousand in each console library, the scale of the challenge becomes clear. And the reality is that success is highly concentrated. Last year, over a fifth of all mobile games revenue was captured by just 100 titles—the top 0.0001% of the market.

In such an unpredictable market, publishers have little choice but to hedge their bets and keep churning out new games in the hope of hitting it big, ruthlessly culling those that don’t make it. So while the cost of making any individual game is modest by comparison to a traditional AAA title, mobile games publishers still face formidable development costs across their portfolios—even before marketing spending. And given the less engaged profile of mobile gamers, aggressive paid marketing is virtually the only available channel for attracting players, at a cost that frequently vastly exceeds the core development budget. What’s more, much of this user acquisition spend goes on advertising in other mobile games—further feeding the marketing budgets of competitors, and fueling an upward spiral in user acquisition spending.

Making games development pay

Given these challenges, many more studios across both AAA and mobile will undoubtedly be bought by first-party publishers and other deep-pocketed giants (see not just this year’s big deals from Microsoft and Sony, but also Netflix’s recent mobile game studio acquisition spree). Others will look to new monetization models. Randomized reward systems, subscriptions, battle passes, and more have proliferated as the search for new revenue streams intensifies, as has in-game advertising, which Omdia estimates now accounts for over a third of mobile games revenue and is set to become much more common on console and PC as well.

Costs can be targeted directly too. After the Cyberpunk debacle, CD Projekt Red announced it was abandoning its in-house game engine and is moving to Unreal Engine for its next project, which it hopes will reduce costs and make it easier to hire engineers familiar with a standardized platform. Expect to see more of this in future, and not just for game engines. Third-party and open-source tools in areas from testing to analytics to backend infrastructure are becoming more prevalent. In principle, these should be more efficient than each studio developing its own solutions. In the longer term, AI-assisted development tools hold out the promise of dramatic increases in productivity.

In fact, almost every trend we see in the games industry today—from the frenzy of studio acquisitions, to the constant search for new revenue streams, to the proliferation of startups offering games tech solutions—can be traced back to the cracks that are growing ever clearer in gaming’s traditional economic model. Many of the paths the industry is taking may turn out to be dead ends, but the continued demand for games is reassuring. Despite its structural problems, this remains a growth industry, and there are enough potential solutions on the horizon to allow for cautious optimism about the chances of eventually finding a better balance.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like