Taking a peek behind Hidden Door's AI

CEO Hilary Mason talks about what generative AI can (and can't) do for storytelling in games

Generative AI is the speculatively disruptive trend of the moment, inheriting the title from the metaverse and blockchain gaming before it. And while narrative gaming start-up Hidden Door just surfaced last year with a pre-seed funding round, CEO Hilary Mason had years of experience working in machine learning and AI beforehand.

And while she clearly believes in the technology's potential – as evidenced by co-founding Hidden Door in the first place – she finds some of the hype around the field of late overblown.

"I'm a bit of a pragmatist in this space," she tells GamesIndustry.biz. "I do believe the technology can be incredibly useful as a tool, and a lot of the applications I see being developed right now are essentially productivity tools around, 'Can we more efficiently do the things around games and entertainment that we're already paying somebody to do?'"

That approach can work very well if the model in question already contains every possible version of the content you're looking to create, she says. As an example, she suggests AI-powered writing of weather reports could work because whatever the day's weather is, it has likely happened before somewhere at some point.

"But when you do see weather that is novel, which unfortunately we're seeing too much of right now, it has no idea what to do," she says. "That as a principle can be applied to the kinds of content work where this technology can actually be useful.

"If you're doing something [with AI] that requires some sort of insight in a broader context... you're going to hit certain limits"

"If you're writing something that has been written before and there's no really unique human insight that you need to pull out of it, it can be a useful tool for that. But if you're doing something that requires some sort of insight in a broader context, some sort of extrapolation as to what could be useful or reasonable, you're going to hit certain limits.

"That's a long way of saying I think there's a lot of hype right now, and a lot of angst derived from hype that is not matching the reality of what the systems are actually capable of, or the work you have to do to make them useful practically."

That angst she alludes to is the concern about AI costing people's jobs. We suggest that the angst is coming not from a fear that AI could do these jobs better than humans so much as it is coming from how eager some employers seems to be to replace humans with algorithms and large learning models.

"Yes, and that's really the thing," Mason says. "They are eager to replace you with something they have never actually seen work in that way. Because it's a lot of energy based on hype and sales pitches that I don't think we've seen substantiated yet… Even if those systems catch up – and there's a very fair question in terms of where they will have impact on certain kinds of work and labor – I do not believe they will wholesale replace most professionals. They will change things. They will change the balance of cognitive labor in certain areas, and that's something that then creates the question of how do we do that in a way that is equitable?"

![A series of illustrated cards labelled "Pale Moon," "Pact" [with the devil], "The Wizard of Oz," "Dead Moon," and "Slitherspace," with the words "Choose your world" above.](https://assetsio.gnwcdn.com/hiddendoor_kp1VkGU.jpg?width=720&quality=70&format=jpg&auto=webp)

Wholesale creation of new stories is one of the areas where you might see a lot of skepticism around the potential of generative AI, but Mason says that's not exactly what Hidden Door is doing.

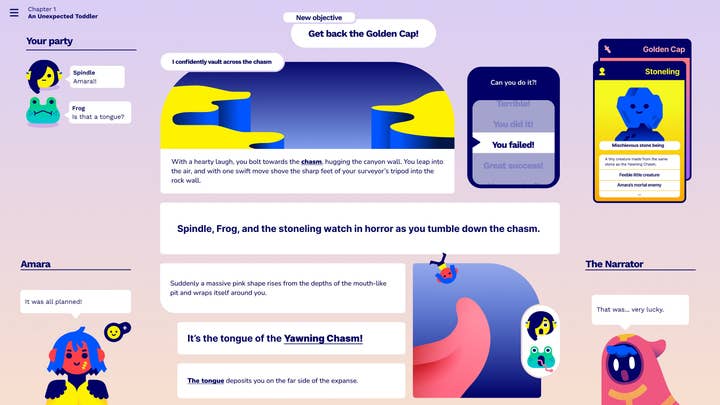

"What we've built is a system that can take an existing work of fiction – like a book, a movie, a TV show – and make it automatically into a playable social RPG," she says. "And from our players' perspective, they come in, choose the world they want to play in, make a character, design the kind of story they want to have through this thing we call our conjuring experience, and then the gameplay happens."

Mason likens the gameplay itself to a webcomic that is generated as people play a game that combines elements of collaborative improv exercises and tabletop gaming. Each player is given a set of cards at the outset, each one could be a character, a vibe (romantic, comedic, horror), or a genre (cyberpunk, for example), and by playing those cards they can adapt the story.

"Cards are a very familiar metaphor for most game players today so they get it easily, but it's also our way to give them a way to choose," Mason says. "It's our way of giving them control of what part of the world or story they want to explore next, and it's also a way to constrain the possibility space."

Hidden Door also lets players choose actions from a sort of multiple choice autocomplete menu where they can type a specific word to search through a list of generated options.

They did try an open text box interface to let players type whatever they wanted, but found it to be a "terrible" user experience compared to giving players limited possibilities and letting them guide the story within those.

And while it may benefit the company to be involved in the buzz around generative AI of late, Mason says Hidden Door is not just ChatGPT with a gaming veneer.

"Everyone I know who's building a product for a game in this space ends up building so much around the large language models to create boundaries on what kind of experience they might have before it becomes a successful product or game," Mason says.

For Hidden Door, a chunk of that work has been put into creating a storytelling formula, for lack of a better word. They have tried to boil down stories to specific templates – Mason gives "a journey story" and "a surprise story" as two examples – and have defined thousands of specific tropes for the system to implement if it fits the rest of the story. (For example, a "child's doll with no eyes" trope might fit a scary theme or a setting like a haunted mansion, while a "bar brawl" trope might fit story elements like inebriation or found weapons.)

Of course, a pile of themes and objects and tropes isn't enough to make a good story; Hidden Door has to use them properly for them to have the desired effect.

"If the story is too chaotic, it is not fun," she says. "On the other hand, what we essentially have built is an engine that can predict at every point in the plot what should happen next, and if we only do that, it is the most boring story in the world. So for us, it's navigating that ratio of 'I get what I expect and then I get a surprise' and tuning that."

"It is a series of tricks that really give the players agency and experience, and balance the familiarity of these tropes... with the right amount of surprise and drama and challenge"

But Hidden Door is the latest in a long line of companies looking to crack the code around infinitely entertaining computer-generated storytelling, and its predecessors haven't had much success. But between machine learning and other, older techniques, Mason believes that can have success with a new approach to the problem.

"It is a series of tricks that really give the players agency and experience, and balance the familiarity of these tropes in the context of the world and story they're in with the right amount of surprise and drama and challenge," Mason says.

She notes there's even a "very light" RPG system under the hood, effectively rolling dice and testing character stats, even if it's not something players will be expected to adopt optimal strategies around.

Considering the legal provenance of model-trained material is one of the bigger concerns of generative AI, Mason emphasizes that Hidden Door will be working in collaboration with authors, and with their permission. (The group is using the public domain work The Wizard of Oz for its proof-of-concept efforts.)

Part of that is key to Hidden Door's business model. The game is intended to always be free-to-play, but the company hopes to offer a content marketplace where players can find fictional worlds to play in, and the revenue from that marketplace will be shared with the creators of those worlds. But as much as brands might be eager to be on the forefront of new tech trends, that might be tempered by the generative AI's tendency to date to swerve toward racism, toxicity, and other things brands would generally prefer to avoid.

"Each IP has rules, which we call the laws of physics of the world, and they want confidence those will be respected," Mason says. "So you can go to ChatGPT, put in your favorite movie and have it give you a little bit of role-playing in that world, but it will go off those rails."

A big part of the Hidden Door sales pitch to brands is about giving them the confidence their worlds will still be safe with its AI-assisted storytelling.

"LLM without rails can go to some pretty harmful content, and that's something we care about mitigating," Mason says. "So making sure they're confident in the controllability and happy with the safety of the experience they're putting in front of the players. And then it's really thinking about how this becomes an additional way for their fans to engage when they're not engaged with the primary book or movie.

"It's not competitive with the book... but it is a way for fans to bring their own creative energy to playing in that world"

"It's not competitive with the book – we'd never think we could write another chapter in a novel – but it is a way for fans to bring their own creative energy to playing in that world. And that's something that's pretty fun and compelling on all sides."

As for other parts of the business model, Hidden Door is hoping to one day open up the marketplace for user-created content, and Mason envisions the game running on a Discord model where people playing on a server together can boost the server and provide benefits for everyone, like different kinds of plots, or having more than one player character per person.

We ask about the added cost of the LLM elements and how that might impact a free-to-play business model. Mason says "it's a cost we're mindful of," but notes that Hidden Door uses a number of models that run in memory or on inference from the CPU.

"We do a lot of pre-generation, so our costs I think are much lower than folks who take the approach of just cramming it all into one large language model and doing chained inference on that," she says. "We're not doing anything magic, I think we're just being fairly thoughtful about where we want to have certain additional controllability boundaries versus where we want the freeform LLM magic. And we're also training our own models trying to be smaller as well, so that gives us another advantage."

Like much of generative AI's impact on game development, that economic element is largely untested. But where that lack of certainty would give many pause, it seems to be part of the appeal for Mason.

"We're in this moment where a lot of people are trying to figure out what becomes possible because of this real technical change," she says. "I think this is a really interesting moment broadly, both on the human side and the experience side. It's a good moment to be thinking about this stuff."

Hidden Door (the company) expects to launch Hidden Door (the game) this winter.