Deep Dive: Player-centered narrative design in Slay the Princess

By building the foundations of our games with player agency in mind, we can better take advantage of our medium and build meaningful experiences that connect with even more people.

January 18, 2024

Game Developer Deep Dives are an ongoing series with the goal of shedding light on specific design, art, or technical features within a video game in order to show how seemingly simple, fundamental design decisions aren’t really that simple at all.

Earlier installments cover topics such as creating a game manual that accommodates multiple learning styles with director of The Banished Vault Nic Tringali, how Mimimi games crafted the save scum-friendly save system in Shadow Gambit: The Cursed Crew, and the technical work and creative nuances behind Slime Rancher 2's new weather system and the experiential impact that developers Monomi Park designed for players.

In this edition, Tony Howard-Arias, lead writer at Black Tabby Games discusses the team's approach to complex player-driven narratives in Slay the Princess.

Making a video game is, at the core of things, an act of collaborative storytelling between you (the developer) and a multitude of people you have never met before, and who you probably never will meet. This remains the case even in games with linear narratives bereft of significant player choice and even remains true for games where there is little to no plot whatsoever—even a round of Tetris tells a story of successes, failures, plans, and accidents.

All of this is to say that if you work in games, you are, on some level, a narrative designer, and our job as narrative designers is to not only make stories that function across a broad range of player styles, experiences, and identities, but that are elevated by this breadth of our audiences. This doesn’t mean that you can’t write a compelling game narrative that’s dear to your heart as a creator, but there must be room for exploration and self-expression within that narrative.

Abby and I started Black Tabby Games with the idea that narrative is such an important part of game design that a well-written and sufficiently reactive narrative can be enough on its own to make a successful game. We also knew that while writing and art were our strengths as a team, we didn’t have the skills or expertise to design fun gameplay, so we quickly decided that visual novels would be our medium of choice.

Scarlet Hollow, our first (and still ongoing) game is an episodic horror-mystery game set around the funeral of the player’s estranged aunt. The player character is nominally a self-insert for the player, and we allow them to select two “traits” in character creation that open up a wide range of flavorful dialogue options and decisions over the course of the playthrough. This is heightened by large amounts of reactivity, including nearly 1,700 individual choice menus and character dynamics written around a 5-axis relationship system. (I’ve already written at length about how character relationships are handled in Scarlet Hollow here, if it interests you.) The end goal is an immersive system of participatory storytelling that works with, rather than against, our players, where the game world, characters, and story are a partial reflection of their perspective while still adhering to the same overarching structure and story beats.

Slay the Princess, our most recent release, started as an experiment to see just how far we could take our studio’s narrative design philosophies if we shrunk the stage of our story as much as possible. What follows is a breakdown of how scenarios and relationships were designed, written, and coded for the game.

(Spoilers for Slay the Princess below. If you haven’t played it yet, I’d recommend doing so before you proceed, and I’d recommend playing the game instead of watching a playthrough. Or find a torrent if you can’t afford it.)

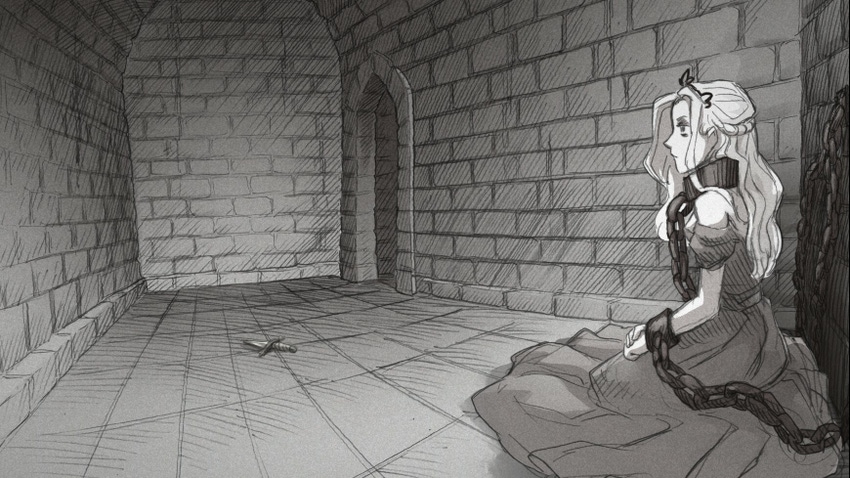

Slay the Princess opens with a simple set-up: “You’re on a path in the woods. And at the end of that path is a cabin. And in the basement of that cabin is a Princess. You’re here to slay her. If you don’t, it will be the end of the world.”

You have a location (woods/cabin/basement), you have a stated “goal” (slay the Princess), and you have a set of characters (the Princess and the disembodied voice telling you to slay her, conveniently named the Narrator.)

As you’ll find if you proceed to the cabin, there’s also a “pristine blade” in the cabin, which is the implement you’ve been given to save the world.

One of the benefits of working around so few moving pieces is that it allows us to explore a wide range of branching decisions without impossibly overwhelming us with exponential scaling. At every major inflection point, we were able to ask ourselves, within reason, what a player would reasonably want to do in that situation, and then carve out a new branch exploring that idea. For instance, in the woods, we can present players with the option to immediately defy the narrator by rejecting the game’s central encounter, and if the player does reach the cabin, we can split the narrative yet again into separate branches depending on whether or not the player takes the blade with them.

An important detail that the initial setup doesn’t share with the player is that the Princess is a perception-based entity. That is, she takes the form of whatever others believe her to be, which in this case, is a Princess (since you’ve been told as much.) This allows us to further shape our branches around the emotional intent of each decision. Returning to the fork where the player decides whether or not to take the blade with them to the basement, we can further color our splits along the following directions:

By taking the blade, the player assumes there’s some level of truth to the Narrator’s premise. They may not have decided if they’re going to slay the Princess yet, but they have doubts about her trustworthiness, and assume that talking to her carries some level of risk. This means that taking the blade downstairs results in a more confident and aggressive version of the Princess.

By not taking the blade, the player more directly rejects the Narrator’s premise. At the very least, they doubt the Princess is an immediate danger, which means that the version of her that they meet is meeker, shy and demure.

From here, there are several major decisions that branch again from each of our world states. The player, in either scenario at the cabin, can choose to talk to the Princess before making a decision (which ironically, by providing new information, can further shape their perception of her, and in turn, can further change outcomes.) They can also attempt to rescue her, attempt to slay her, or attempt to lock her away in the basement.

With the exception of one outcome, all of these choices ultimately result in either the world’s end or the player’s death, and Chapter 2 starts, revealing part of the game’s structure to take place within a time loop.

Because of the Princess’ relationship with your perception, each of these outcomes results in an entirely different Chapter 2, and we take a similar approach from there, but more on that in a second.

An extremely rough map of the first chapter of the game looks something like this:

.png?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

Images via Black Tabby Games.

We had a set of themes in mind when we started work on Slay the Princess. We knew we wanted the game to be about relationships, and perception, and particularly about the intersection of those two things—about how difficult it can be to truly know someone without the very act of knowing transforming them into something else. And by putting ourselves in the shoes of our players while laying the groundwork for the game, we were left with a set of Chapter 1 endings that gave us a diverse set of opportunities to more deeply explore variations of those themes.

To give some examples:

By fleeing the woods in Chapter 1 and rejecting the core premise of the game, the player never actually meets the Princess before the world ends. This gives us The Stranger, an exploration of trying to know someone Other that you will never be able to understand.

The Adversary results from the Princess and an armed player mutually killing each other in combat, leading to a route exploring rivalry and its intersection with passion.

By refusing to pick up the blade and rescuing the Princess while ignoring various warning signs present in the text, the player faces the Damsel, an exploration of standard damsel-in-distress tropes in the face of cosmic horror.

By narrowing the thematic focus in Chapter 2, we were able to stave off some of the more aggressive scope creep that would come from having so many distinct chapters. Since each Chapter 2 was about something, we were able to reframe our narrative structures around the decisions that would have already led to a given chapter. The Tower, for instance, with its themes of submission and loss of agency, let us directly take control away from players are key moments as part of the narrative (greying out options that could have hypothetically led to different outcomes.)

.png?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

Images via Black Tabby Games.

Supporting these narrowing themes is another mechanic: the voices in your head. These voices were first introduced in Chapter 1 with the “Voice of the Hero,” an embodiment of the player’s conscience (a natural tendency to resist doing evil) and their intrusive thoughts. This second part is particularly important to the narrative structure of Slay the Princess. While the Princess’ identity changes in relation to the player’s perception, we as game writers don’t have a direct pathway to our players’ thoughts, which put us in a difficult position where we could either ask our players for those thoughts (a big, immersion-breaking no-no in our book) or to find a way to vocalize thoughts that were at least tangential to whatever decisions the player has just made.

So, in Chapter 1, if we think a decision should create doubt, we can use the Voice of the Hero to express that doubt and unobtrusively make it a part of the player character.

Much like the Princess transforms into an entirely new identity in Chapter 2, we also took the player’s revival as an opportunity to add a second voice we could use to express ideas and emotions related to their previous actions. A player who slays the Princess in Chapter 1 immediately and without asking questions, for instance, acquires the Voice of the Cold, an emotionless and violent addition to the chorus. And we, in turn, are able to use these voices to further shape the player’s choices as well as the Princess’ form.

As an example, bringing down the knife in Chapter 1 (expressing skepticism towards the Princess’ intentions) while ultimately freeing her (expressing skepticism towards the Narrator’s intentions) unlocks the Voice of the Skeptic and takes you to the Prisoner chapter. When presented with the blade at the beginning of that chapter, the Skeptic insists that the player takes it, forcing them to act in line with their previous choices, while also reducing the exponential scaling related to that chapter significantly.

Upon reaching the logical climax of a full narrative, the Princess is taken away from the player and they are brought to the hubworld of the main narrative, a place called The Long Quiet. Here they meet a gestating entity connected to the Princess, and are sent back to the beginning of the game with a quest to bring this entity more “perspectives.” This metanarrative allows us to do a few things:

It allows us, again, to avoid the worst consequences of exponential scaling—individual stories can be brought to an end relatively quickly.

We’re able to push players out of their comfort zones and explore more avenues.

We’ve created a framework to directly tie everything together through the narrative’s overarching themes while retaining player agency within that structure.

At the end of the day, Slay the Princess is built around and guided by player choice. As game writers, we will never be able to see directly in our players’ heads, nor will our players be seated directly at the writer’s table. But by building the foundations of our games with their agency in mind, and by looking at our work through their perspectives throughout development, we can better take advantage of our medium and build meaningful experiences that connect with even more people.

I hope this breakdown has been helpful to you! If you’re interested in more of the writing I’ve done on narrative design and managing an independent studio, please feel free to check out my devlog.

Read more about:

Deep DivesAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like