Immersing players in the culture of a people with language puzzler Chants of Sennaar

Julien Moya of Rundisc delves into weaving whole cultures and peoples to educate the player on unknown languages.

The IGF (Independent Games Festival) aims to encourage innovation in game development and to recognize independent game developers advancing the medium. Every year, Game Developer sits down with the finalists for the IGF ahead of GDC to explore the themes, design decisions, and tools behind each entry. Game Developer and GDC are sibling organizations under Informa Tech.

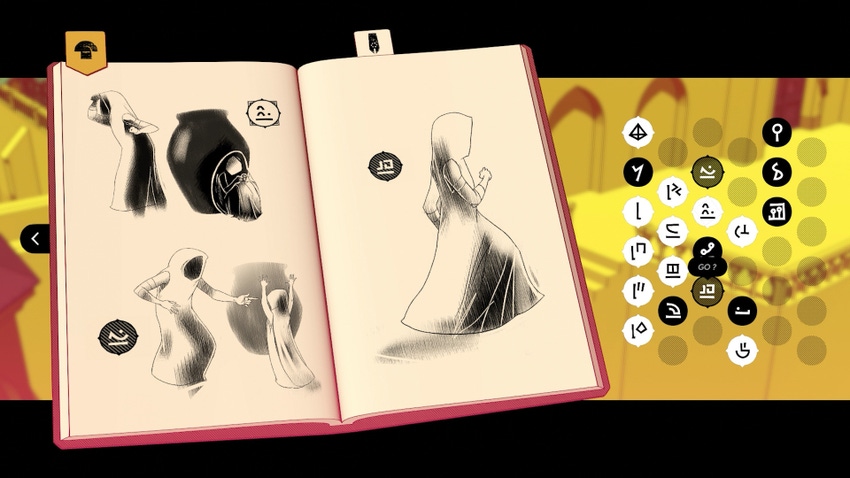

Chants of Sennaar captures the experience of being in a land where you don’t speak any of the languages, having you pick up what you can by observing and interacting with the people and world around you.

Game Developer spoke with Julien Moya, art director for Rundisc, to talk about weaving whole cultures and peoples to educate the player on unknown languages, being willing to pit the player against challenging linguistic puzzles and covertly giving them the tools to succeed, and the importance of setting up visual “rules” to create clarity for the player when they’re trying to figure out something complex.

Who are you, and what was your role in developing Chants of Sennaar?

I'm Julien Moya and I'm the art director of Rundisc. I created all of the graphical aspects of the game. My associate Thomas Panuel and I designed the game together, and he coded it.

What's your background in making games?

During my 20-year career as a freelance graphic designer, I have created a few small games (especially in the field of advergaming) and participated in a few studio projects of varying sizes. But the first really ambitious project I worked on was Varion, which was also the first Rundisc game I created with Thomas. After that we started the development of Chants of Sennaar.

Images via Focus Entertainment

How did you come up with the concept for Chants of Sennaar?

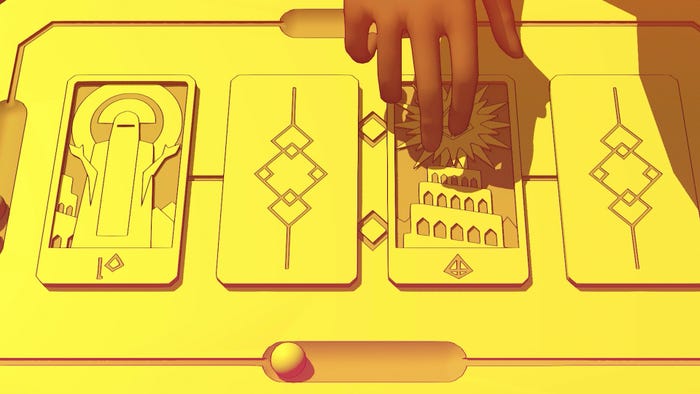

We started by developing an original visual universe inspired by the architecture around us, with the idea of making a highly cinematic puzzle game, a bit like Inside. It was only later, thinking back to Heaven's Vault (which I had played a few months earlier), that I came up with the idea of making the game revolve around languages. From that point on, we took a decidedly puzzle-oriented turn, drawing inspiration from titles such as Return of The Obra Dinn, Outer Wilds, and The Talos Principle.

We decided to take this concept as far as possible by creating not just one dead language, but several interconnected living languages to be learnt through observation and interaction. The guiding idea was to reproduce the feeling of the traveler who explores countries where he or she doesn't speak the language, and ends up gradually understanding it purely through cultural immersion and practice. From there, the idea of having several peoples was born, and the rest of the story followed.

What development tools were used to build your game?

We mainly used Unity as well as a few third-party tools like Wwise and Rewired. We didn't use anything other than standard tools, and we coded all our shaders ourselves.

You delved into much of your process in creating these languages in a previous Deep Dive with Game Developer, as well as how culture and language mingled in intriguing ways. How did you develop the systems around letting players work out and retain what is being said in each language?

The most difficult part of the project was defining the core design of the game, i.e. what the rules and possibilities would be, and what tools would be available to the players. Very quickly, we knew what kind of game we wanted to make, but we couldn't figure out how to turn that into functional and, most importantly, fun gameplay. Sometimes it was way too easy and sometimes way too hard.

It took a lot of trial and error to come up with the best compromise: a gameplay loop that worked. It was even harder because we were trying to create gameplay that didn't exist, so apart from a few specific elements (like the Obra Dinn-inspired validation system), we didn't have any models to follow. For a long time, we weren't at all sure that a game like this could work. Fortunately, after a lot of thinking, we came up with the solutions we'd been missing — the few rules and systems, like the annotation tool or the automatic translation of complete sentences, that made it all possible. From then on, development was quite smooth.

Images via Focus Entertainment

Chants of Sennaar quickly teaches the player a few simple phrases using some of its puzzles. What thoughts went into choosing the baseline words you wanted to teach the player? What thoughts went into creating a situation to teach those words?

Finding the right corpus of words for each language was a task dictated by scenario and gameplay imperatives: what words did each language need to tell the story of its people, create enough puzzles, and ultimately allow the peoples to communicate with each other? Building these corpora was a fairly lengthy process during the writing of the game, as they had to satisfy a huge number of overarching constraints, and required the creation of all the races, dialog, puzzles, and even level design at almost the same time. It took many iterations to get all these alphabets to work together and with the scenario in a coherent and satisfying way. Right up to the end of writing the game, words were still replaced by others to make everything fit together.

In comparison, creating puzzles to learn these words (or, conversely, puzzles that exploit the learning of these words) wasn't very complicated. Probably because there were already plenty of examples and games in this area to draw inspiration from.

The work on the situations themselves was particularly interesting though, as we had set the rule throughout the project that all situations had to be coherent, justified, and in-keeping with the world and its history. As in Outer Wilds, the player evolves in a functional universe that follows its own rules and exists with or without them. In Chants of Sennaar, every puzzle, every NPC, every object has a very good reason for being there. The situations are those of the everyday life of the beings that populate the Tower. I think that's where a lot of the enjoyment comes from, because you have to understand the world around you—the history and the lives of the characters you meet—to understand their language, not the other way around. That's why Chants of Sennaar is not a "simple" puzzle game, where you just decipher symbols one by one, but a real cultural immersion into a world, an exploration, a journey. I think that's what players remember and appreciate.

What challenges come from putting the player in situations where they may not know what the other characters are saying yet? How do you guide the player when they may not have any idea what is being said to them yet?

Another important rule we made during development was based on redundancy: every word you encounter in the game must be seen at least twice in two different situations (most of the time it's much more than that) to give you multiple opportunities to understand it and check your assumptions. In Chants of Sennaar, it's perfectly normal not to understand a word the first time you see or hear it, and you're not encouraged to try too hard to translate it on the spot. On the contrary, you're expected to jot down a few hypotheses and keep exploring until you find other contextualization of the word, even if you sometimes have to go back to refine your deductions. Except at the very beginning of the game, the player is not really guided, except by subtle means of simply drawing attention to this or that element, situation, or clue.

One of the virtues of this system is that it's very adaptable. Of course, we did a lot of playtesting during development, and sometimes certain words or parts of the game were definitely too difficult for players. In those cases, all we had to do was to add a few occurrences, a few clues, an additional place or character using a word in a new context that provided a new learning opportunity. By making these small adjustments, we ended up with levels that could be completed by just about anyone, while still maintaining the fun of doing it yourself.

Images via Focus Entertainment

What difficulties came from potentially overwhelming the player with too many new words or symbols? How did you work to keep the player from having to figure out too many symbols at once?

The number of words that are likely to remain untranslated in the journal at any given time is one of the variables we've used in the game to gradually increase the difficulty. It's very easy to translate 3 words in the diary when you only have 3 unknown glyphs on your keyboard, like at the beginning of the game. It gets much harder when you have 12 words to translate, like at the beginning of level 3. In fact, we didn't set out to ensure that players would never be overwhelmed by this difficulty. We just played with it on purpose. If the player feels completely lost at certain points in the game, it's because that's precisely the experience (of being a lost traveler in a foreign land) that we wanted to create. So, the important thing is that all this is controlled, and in fact this goes to the heart of game design, which for me is a discipline of illusionism.

It's like when you're in an action game and you're facing a 20-meter flame-spitting boss. At first you think, "Oh my God, he's way too strong, I'll never make it". But in fact, the game designers have come up with a whole series of weaknesses, patterns, and tools that make that boss much less powerful than he seems once you've understood a little bit about how to deal with him.

So is the art of game design: confronting the player with seemingly impossible challenges while discreetly giving them all the tools and clues they need to succeed, believing they've done it all on their own. It's this sleight of hand, this pure illusion, that creates the sense of accomplishment and satisfaction that lies at the heart of any good gameplay loop.

As you worked to create your own languages for this game, what thoughts went into designing the various symbols so that they were vastly different from one another so players could easily tell them apart? What challenges did you face in creating so many different words/symbols?

From a graphic point of view, we created languages as different from each other as their peoples. In fact, we proceeded in exactly the same way: by cultural mash-up. The Bards living on the third floor, for example, have a culture inspired by both Arabs and Indians, which is reflected in their architecture and their script, which is a sort of a mix of Kufic and Devanagari.

Then, within a script itself, we've set up little systems that allow us to distinguish structures: certain forms mark a verb, a subject or a place. Some glyphs are made up of several radicals seen elsewhere, and so on. Here again, all these little clues help the player to find their way around, exploiting things they have previously learned.

As with the rest of the game, I think the key here is to be extremely rigorous in the rules you set up and stick to them throughout. This is also something I've learned in graphic design: when you make a rule clear to a user (or, in this case, a player), you then have to make sure it is followed at all costs, without exception. In this way, the player can identify and learn a very large number of rules and rely on them to progressively learn more and more complex things.

Throughout the process of writing the game, we put tools in place to ensure this consistency, with big Excel tables that were systematically updated for each detail we changed. This rigorous approach was essential if players were to "trust" the game and manage to find their way around despite its complexity.

What do you hope players take away from this experience in exploring a culture and world where they do not understand what is being said? From a journey about trying to understand another language?

Chants of Sennaar has no political message or grand moral to assert, only the desire to shed light on other types of heroes than those we are usually presented with. To participate, in a small way, in the creation of new models. People are capable of solving problems not by force, or even less by violence (which, by the way, rarely solves anything in real life), but by empathy, by the ability to understand, to love, and to bring others together. To cultivate what unites us instead of aggravating what divides us, to create bonds. The hero of the game is a scientist, a translator, and a diplomat. That's the kind of hero our future is in need of.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like