Food has been a part of video games for ages, from Pacman to Metal Gear Solid. It has been refilling our health bars, giving us more stamina points, and unlocking extra powers. Despite that and its rich symbolic, cultural, and social meaning, it rarely features in narrative. The rare exceptions are worth a closer look.

Let’s start with Pentiment. I’m quite fond of it because whatever the topic, it turns out to be an excellent case study. It’s a murder mystery set in Reformation-era Bavaria, inspired by The Name of the Rose. Culinary experiences aren’t the focus of the story, but they are important to how it’s told. Playing as Andreas, you’re trying to solve the murders in the village of Tassing. You’re also an outsider. On several occasions, you will be invited to dine with different people. Choosing who to join for a meal - and who not to join - affects how townsfolk perceive you, as well as what clues you can pick up for your investigation.

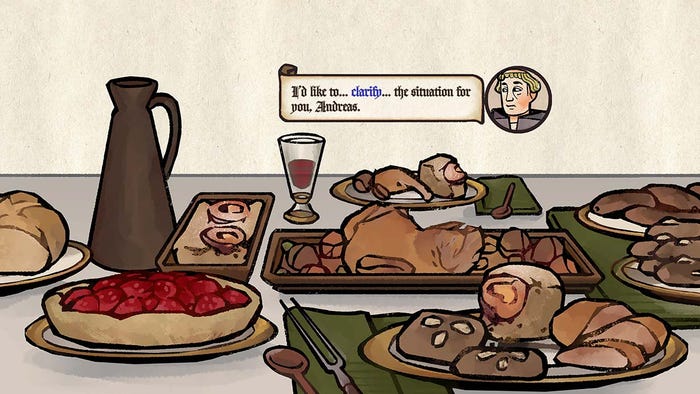

With Andreas and the villagers gathered around a table, you can select dialogue options and what to eat. Meats, cheeses, breads: take your pick, it won’t affect the outcome of the conversation. The interactive bites are there just for flavour (heh, heh) but they bring you deeper into Pentiment’s world. Having a meal together lets you connect with other characters not just because of what they say but also because of the communal aspect of breaking bread. It’s also a clever piece of environmental storytelling. A look at the table - what is served, how much of it, on what plates - can tell you a lot about your hosts and what’s happening in Tassing. Some folks are struggling, while others hoard wealth. And after the local abbot increases taxes, you will notice meals getting meagre in some houses.

Maybe clicking on a slice of rye bread would feel less impressive if it wasn’t so unique. There are dozens of games where I shot, punched, or exploded other characters. Pentiment was the first one where I got to enjoy a meal with them, instead.

Not the first one in existence, though. One earlier example would be Sakuna: Of Rice and Ruin, an unusual combination of a side-scrolling slasher with a farming sim. You play as the goddess Sakuna, banished to an island full of demons. The fast-paced combat is a way to explore the island and gather resources and ingredients. Then you go back to your hamlet to farm and cook. The food heals and unlocks buffs but it’s more than just a system for replenishing stats.

Sakuna eats dinner with other people stuck on the island. Unlike in Pentiment, these scenes aren’t interactive (though characters can react to the specific foods you served) but have similar purpose. They diversify the storytelling and support worldbuilding by giving NPCs personality and backstories. It’s a narrative garnish on top of a mechanic.

The meal sequences in Pentiment and Sakuna are perfect examples of how to do exposition in games. It’s not too much, it’s not too little, it helps the pacing of the plot, and it feels like a novelty. Simply delectable.

What about cooking games, I hear you ask. For those that have a narrative component, it’s interesting to compare Overcooked and Venba. In both, you progress in the story by cooking, which in practice means combining the correct ingredients in the right order. Despite starting from the same place, these two couldn’t be more different. In gameplay, story, tone. In everything.

In the Overcooked series, the Onion Kingdom is under attack by various types of vicious monsters, like the Ever Peckish Beast or hordes of the Unbread. You can only defeat them by mastering the art of cooking. It’s goofy, hilarious, and frantic. Playing Overcooked is like starring in a cartoon version of The Bear. Every second counts, so you dart across the kitchen (which could be in a restaurant but it could also be in a mine because why not?) slicing, cooking, and serving, while also desperately trying not to set the whole place on fire. In co-op it’s that, but the person next to you on the couch is also shouting WHERE ARE THE TOMATOES JESUS CHRIST WHY ARE YOU TAKING SO LONG. In a story about fighting evil with pizza, sushi, and burgers, the gameplay really makes it feel like you are indeed fighting for your life with every dish served.

Venba is the opposite of that. The titular hero is an Indian woman who moves to Canada with her husband in search of a better life. The story spans decades and deals with struggles of immigrants, as well as more universal themes of parenthood, family, and loss. In each chapter, Venba cooks. She puts on Tamil music and tries to recreate a dish from an old, smudged cookbook she received from her mother. For the character, it’s a way to connect with her roots. For the player, to take a breath and think about the story. There’s no ticking clock, no score, no punishment for getting it wrong. It’s just you figuring out the recipes at your own pace to the background of the music and sizzling oil, hissing steam, and sloshing water. The game’s sound designer, Neha Patel, actually made all the dishes herself and recorded it, to wonderful effect. The cooking remains cosy and pleasant even when the story pulls at your heartstrings. In one of the later chapters, ageing, widowed Venba is waiting for a visit from her adult son. You make an elaborate, multi-dish meal for him and he cancels last minute. It’s as mundane as it is heartbreaking.

An idea for a game about cooking took vastly different shapes with Overcooked and Venba. It goes to show how much more there is to discover with food as a narrative tool and not just a mechanic.

There’s also something to be said about how online co-op games use food to give players a communal activity disengaged from main objectives. In Deep Rock Galactic, you can have some beers and get drunk between missions. In base-building games like Valheim and Sons of the Forest, food is necessary for survival but cooking takes time. Waiting for soup to boil, you can just hang around with friends. But this is a part of a broader conversation about how multiplayer games facilitate emergent narratives. I’m going to leave it for dessert.

If you enjoyed this post, visit my blog Narramblings for more musings on narrative design and game writing.

Thanks to the Writing Interactive community for pointing me towards some games mentioned in this post.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like