Puzzmo co-creator Zach Gage on building newspaper games that can last forever

"Every game I design is meant to be a sandbox. At the lowest level, someone coming in should just feel comfortable playing around."

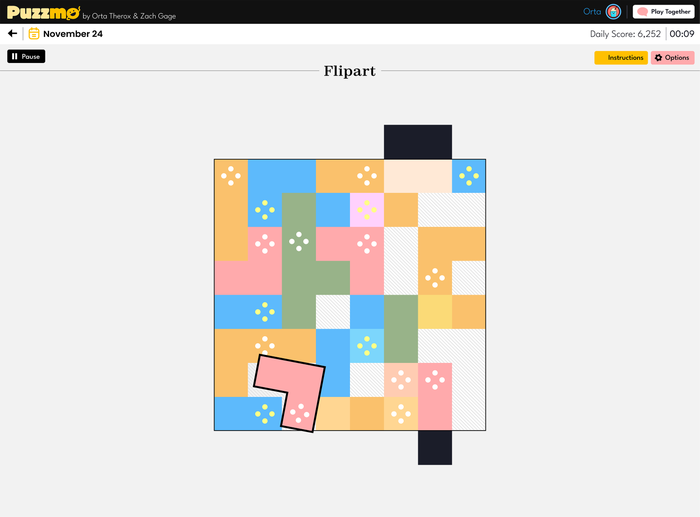

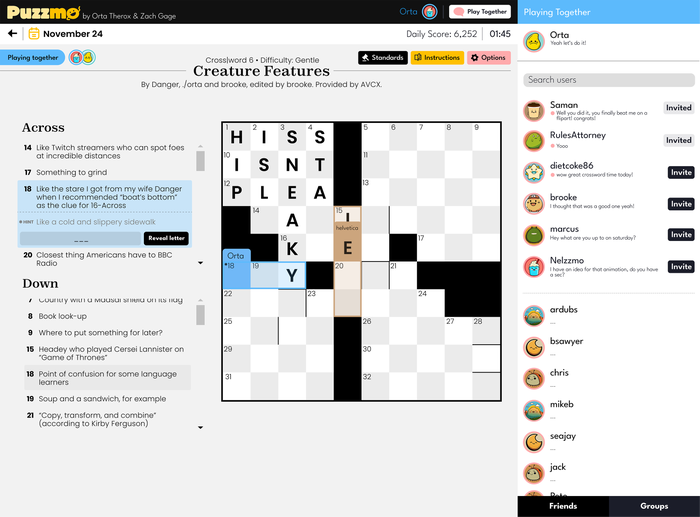

Award-winning game designer Zach Gage wants to reboot the newspaper games page with Puzzmo. But as much as the new platform, which invites players to kick back and peruse a selection of daily puzzles like Really Bad Chess, TypeShift, Flipart, and Cross|word, is a place for games—Gage tells us it's also a place for people.

The veteran developer, who began crafting Puzzmo with the aid of lead engineer Orta Therox (although the team has since expanded significantly), explains he first began thinking about how one might reinvent newspaper games for a modern audience a decade ago after he was invited to meet with The New York Times. Those talks eventually broke down, but Gage continued to fixate on how he'd make a crossword more approachable in a digital era dominated by blockbuster video games and algorithmic social media platforms like Twitter (now X), Facebook, and TikTok.

The answer is Puzzmo. During a wide-ranging interview earlier this month, Gage explains the platform "grew out of some frustrations in having to work within other people's frameworks." He notes the rapid monopolization, decay, and fragmentation of platforms like Twitter, which so many creatives with a online presence have come to rely on, persuaded him to pull the trigger on Puzzmo and create a bespoke space that allows him to champion his own creations while enabling puzzle aficionados to put down roots.

"It felt like, alright, maybe if we can just build our own place to do our own work then I won't have to [rebuild my online presence on other platforms]. I can get out while I still have reach," he explains. "For years, people older than me have been saving 'oh, you've gotta own your audience.' That's a gross way to say it, but what they're saying is 'you've gotta own your capacity to reach them.' If somebody else owns your capacity to reach an audience, you're always going to be beholden to their whims, and so one of the other questions with Puzzmo was 'how do we move to a place where we have that?'"

Puzzles for the people

Puzzmo has launched under the ownership of newspaper company Hearst and was developed with financial assistance from Astra Fund. Gage says the involvement of both was critical, not least because they aren't targeting "exponential growth."

"The goal with Puzzmo is to build the world's best puzzle website that is run as a very successful and very profitable business forever. I think that puts us in a very different spot than if we had, instead of going with Hearst, gotten a bunch of venture capital from venture-backed firms that want exponential growth and want to throw billions and billions of dollars at us right away. [...] None of that is happening."

Right now, Puzzmo is employing a "slow growth strategy" that enables 500 new players to access the platform each day (if they can prove their puzzling prowess). Many of the daily puzzles are free-to-play, but additional puzzles and features such as leaderboards, groups, and archival access are exclusive to annual or lifetime subscribers. It's a model Gage hopes will enable the Puzzmo team to gather its bearings while nurturing a tight-knit community. "We want to build a really great product, get an audience, compel that audience to subscribe and support us, and then build out our features to make sure everybody is happy," he says.

As for how Gage will compel puzzmonauts to come along for the ride, he intends to create "thoughtful" puzzles designed for all. In practice, that means seeking to understand why he connects to a certain experience before helping others do the same. Discussing his personal design principles ("we're getting really into armchair philosophy here," he tells us), Gage explains that compelling, approachable design involves truly contemplating why people find something interesting in the first place.

"'Interestingness' is how many connections an idea has in your brain," he says. "So if you see an idea or learn something new, the number of things it connects to is how 'interesting' it is. Things that are real epiphanies are ideas that pop up and connect to a lot of stuff, despite you never having thought about it before. It fills a little hole and spider-webs from there.

"If you think about what it means to appeal to somebody, then, what you're really doing is connecting to a bunch of priors that somebody has. When somebody doesn't find something interesting, it actually means they don't have enough priors to care about it. Your response is to either back up and set up more priors to bring even more people in, or you can just try and appeal to the people who've had those kinds of experiences. So much of game design is just setting somebody up for an expectation and then delivering something based on those expectations. That's what games are."

Every game is a sandbox

Gage notes that even when an idea resonates, you still have to account for different skill levels. "Difficulty and expectations are not really linked," he explains. For instance, someone could be terrible at crosswords but still be incredibly excited by the prospect of completing one—perhaps just as excited as someone who lives and breathes the word-weaving conundrums.

Taking that into consideration, he says that solving the difficulty problem requires "thinking about 'how do I support the player who has nothing? And how do I support them in a way they expect so they use the support?'" The second consideration then becomes how can you support someone playing at a higher level in a way that doesn't make them feel encumbered by the structures you've put in place?

"Every game I design is meant to be a sandbox. At the lowest level, someone coming in should just feel comfortable playing around, and through playing around they should be able to understand what's exciting about the game," he explains.

"The more they understand, the more they should start to realize the affordances and constraints of the sandbox and naturally start applying them in their own play. It's like 'oh, there are buckets in here! I can use buckets to make sandcastles. Okay, how many sandcastles can I make? But there are only so many buckets and I only have so much time!' [...] By the time you put all of those constraints on yourself, you find a really complicated, really deep, exciting game."

That desire to let players freewheel means a lot of Gage's puzzles–such as Really Bad Chess and Typeshift (which you can play above)–often shun unique solutions. It's an approach that defies more "traditional" puzzle design in service of asking players to think critically.

"When you have a traditional puzzle that has a unique solution and a unique path—like say if we were talking about The Witness, which I think does this very well—you have to be very thoughtful about how you deploy those puzzles to players. You have to make sure they understand every concept and that you're always going to give people a puzzle that is exactly the right difficulty," he says.

Gage believes those puzzles are born out of a very specific type of learning that was popular in the '90s and '00s, but says it's not how he's interested in teaching. "For me, I'm interested in getting people to have strong critical thought capabilities, to be good problem solvers, and to be able to tackle a situation that's unknown and tackle it in their head. [...] It's a sort of bottom-up approach instead of the top-down approach of being given a textbook of examples that you're going to work your way through slowly."

Into eternity

Initially, all of the games featured on Puzzmo will be developed by Gage. Some might be existing works that have been adapted or tweaked with Puzzmo in mind and others might be entirely new creations. The long-term aim is to have every project that lands on Puzzmo stand the test of time, and that means Gage is wary of admitting titles that have been focus-grouped into being.

Elaborating on that point, he explains "rubber-ducking," which is the act of designing something for a hypothetical audience, is commonplace in game design—but it's a technique he personally avoids. He concedes that failing to understand that particular school of thought is entirely his own problem, but he still can't shake the feeling that setting out to craft an experience for a specific subset of players is an act of creative self-sabotage.

"[Some people] will put a hypothetical rubber duck on their desk and pretend it's somebody they've given a bunch of characteristics to. They might say 'alright, I'm going to make a game for sixteen year old girls who're into castles [...] and every time I make a design choice I'm going to ask that duck, 'is this appealing to you?' I just do not understand how you could make a game with that approach," he says.

"Every time I design a game, the thing that is most important is being able to find something surprising and thrilling and exciting about the design. The nature of something that is surprising and thrilling and exciting is that you could not have anticipated it."

Gage believes we live in a world where a lot of teams rely on rubber-ducking, but suggests those projects can fall flat because someone internally makes a bunch of assumptions about an audience that end up being completely wide of the mark. As for how that relates to Puzzmo, he reiterates that even though there are experimental games on the website, the aim is for every game that features to exist for eternity. That means they can't be designed for any one person or group.

"Hopefully we're going to have enough users that somebody loves everything," he continues. "I don't want to have to remove that thing from that person's life—even if it's just 10 people on the site who love a game." He adds that one of the benefits of championing daily games is that it'll allow the team to spotlight projects that might've struggled to survive as a premium release.

"The big change with Puzzmo—and this was very intentional—is these aren't games that were designed to be played for hours on your couch. What that means is that if a game is fun for 10 hours, it'll be good enough for Puzzmo. Because that's a lot of hours stretched out once a day over a year," he explains. "I've had to throw out so many prototypes that were really fun and cool for 10 hours, and I'm looking forward to not having to do that any more.

"That's a very concrete example of the kind of thing I really wanted to change about the way I was making these games and the platforms themselves. You can't do something like that on Steam. That's not what Steam is built to do."

That doesn't mean Gage is against the idea of welcoming other developers into the Puzzmo family. It's entirely dependent on whether or not the platform can find an audience. The roadmap right now is long and winding, but as Gage himself admits, if you're going to make a plan you might as well include a moonshot.

"We want to have hundreds of thousands or even millions of people [on Puzzmo]. We want a huge audience for this thing, and we're trying our best to scale it up," he says. "Is there a world where we're putting other people's games on Puzzmo? Yeah. If Puzzmo turns into the Steam of puzzle games we'd be thrilled. Is that going to happen? I have no idea."

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like