10 design lessons learned from 30 years of horror games

Developers have shared their techniques and philosophies with us, condensed here for your convenience.

Horror is not just one of the most prolific themes in video games. Its use in an interactive medium is a brilliant opportunity to discuss player psychology, the myth of player agency, how folklore and superstition reflect cultural values and collective fears, and the difficulties of scripting the unexpected. Over the past few decades, many designers and developers working in this genre have shared their methods, techniques and philosophies with us, key lessons which we have condensed and summarized for your convenience. Naturally, the advice here is not comprehensive, or one size fits all. But within these tips, there is some overlap suggesting consensus on some key points that, whatever your approach as a horror game designer, could be a good starting point. Here’s what we learned.

1. Earn the player’s trust, then turn it against them

Pretty much all of Mason Smith’s GDC 2021 talk MORTIS 101: 'FAITH's' Horror Design Toolkit could be used for this article, but one piece of advice stands out: betray the player’s trust. “You can identify spaces that the player considers safe, and then you can invade that,” he says. Some of the most intriguing moments in games, he argues, come from when the relationship between developer and player is disrupted such that the developer is no longer the player’s advocate.

“What parts of the game does the player think does a player think are safe? And how do you invade that?... What parts of the game does a player think is safe? Is it safe room? Is it a particular corridor or hallway? Is it a particular part of the game? It can be tempting to never let the player feel safe like they're always in danger…But I believe in that playful relationship between designer and player, especially in horror. But you have to find those moments, right those vignettes.”

He goes on to describe how he designed the outer areas of the haunted house in FAITH to have a “tree demon,” that would spook the player by moving suddenly when they entered a section of the forest. This particular tree is the only one of its kind, which places the player in a paranoid limbo as they continue to move through the woods. These small moments result in a high payoff.

2. Disempower the player

Many horror game developers have said it before, but it’s worth saying again: don’t let your audience feel too powerful. After all, the point is for them to feel fear. In 2015, Herring Studios narrative designer Michel Sabbagh argued that very thing, saying that limiting the players’ resources is the best way to increase their panic and encourage methodic problem-solving:

“While giving the player tools for means of survival isn’t a bad design choice in and of itself, making said tools extremely powerful will not only make the player potentially reliant on them, but it will also shatter the sense of vulnerability that’s essential in making the experience palpably frightful. The tools that the player is given should have limitations of their own, which will compel the player to approach parlous situations in a more methodical and careful manner.”

3. Consider dropping the cut scenes

In a 2008 interview with Frictional Games co-founders Jens Nilsson and Thomas Grip, the two opined on their work on the Penumbra series and told Leigh Alexander that while some games can benefit from cut scenes, in cases where immersion is important, they can be counterproductive.

"Whenever one shows a cut scene, or somehow locks the player and forces some event, the player is brought back to reality, and some of the immersion is lost. Half-Life started doing this the right way, but still locked and forced the player to wait for some event to happen at times."

"In Penumbra, we had this in mind throughout the design of the game, and tried to narrate the game through the ways puzzles where constructed, by showing evidence of events in the environment, and more. Still, we feel like there is a lot left to be done with this -- and will go several steps further in our upcoming game, Unknown." (That game, Codename: Unknown, would go on to be the influential hit Amnesia: The Dark Descent.)

4. Leverage player psychology

Whitney Beltren’s GDC 2022 lecture Leveraging Player Psychology in 'Bluebeard's Bride' is an excellent primer on applying Jungian psychology to your character writing. Understanding a basic theory of how people structure their sense of self can help identify what their motivations and greatest fears are, whether that’s the audience of your game or a character that you’re writing. She also reveals how this philosophy was applied to Bluebeard’s Bride to authentically and empathetically facilitate what Beltren calls “feminine horror,” that is, an experience rooted in the difficult lived experiences of women. Check out the whole GDC video to hear what she means in context.

5. Leave the players to their imagination

One thing that comes up frequently in discussions about horror techniques is the idea not to overdo it with graphics or visuals and instead lean into the player’s own imagination. In a 2011 interview with Kris Graft, Dead Space 2 creative director Wright Bagwell commented on this, saying,

“The number one thing that you said that's really tough to accomplish with video games is letting the player use his imagination, to let the player think there's more going on than there actually is. So, having sounds that suggest there are creatures in the room with you when there aren't any physically there is one of the best ways to scare players.

People's imaginations are always far more powerful than anything you can put on screen, but the problem with video games, of course, is that you've got to have 10 hours worth of content, and you can only make so many enemies because it takes so long to build them, to concept them, to animate them the right AI for them.”

In other words, don’t sweat it if you don’t have a big budget. That may work in your favor.

6. Relinquish control

Another conversation that comes up a lot on the topic of horror games is the issue of player agency and game scripting, that is, the fact that horror experiences often rely on specific timing. Halloween haunted houses, for example, are rarely designed as open-world; they’re set to a rigidly controlled path. So, how does a designer maintain control? Bioshock designer Ken Levine says you simply don’t.

“You can't. You have to give that up that to some degree. I talk about trusting the player a lot. Information is not your friend with horror. It's missing things. One thing that people on the team kept saying was, "Shouldn't we lock the player in place? What if they miss it?" I said, "That's okay if they miss it. The thing out of the corner of your eye is way scarier than the thing in front of you."

7. Environmental storytelling is your friend

In 2014’s postmortem of Amnesia: A Machine for Pigs, Peter Howell stresses the importance of using the environment to tell part of the story and how it provides the potential for both greater poignancy as well as greater ambiguity.

“The poignancy is critical in creating an affective, emotional experience for the player. The game environment has far greater potential for this than a spoken or written dialogue describing that environment. For example, a single picture of the shoe room at Auschwitz, or of the lone protester facing up to a tank at Tiananmen, are far more arresting, far more powerful images than anything that could be described through words alone.

The poignancy of such environmental storytelling is important. However ambiguity is also a key part of this type of storytelling. Even the above examples offer levels of ambiguity despite seemingly portraying quite obvious events. Each pair of shoes at Auschwitz has an implied life story attached to them for example. The picture of the Tiananmen protestor poses questions regarding his thoughts and emotions at the time the picture was taken. It is these associated implications that assist in the creation of the emotionally affective aspects of a story. The image, or environment, is simply a cue to thought and to consideration, rather than an explicit, closed story…Ultimately, that which occurs in the player's head will almost always form itself into something more disturbing and more horrific than anything the game could explicitly portray.”

8. Subvert the player’s most cherished memories

In general, subversion is an effective and necessary aspect of horror. One popular use is to destroy the audience’s nostalgia and sense of safety by reimagining sentimental memories from their childhood. Five Nights at Freddy’s is one popular example; another is Choo Choo Charles, whose developer Gavin Eisenbeisz told us earlier this year,

“Doing this is really enthralling to people for a number of reasons, all of which make a game more readable and intriguing. It mainly adds a sense of familiarity which gives people an instant connection to your game, as well as a sense of irony, which people find amusing and memorable. This makes the game stand out and is huge for branding.”

9. Keep it real

Like the show that inspired it, Deadly Premonition was disruptive and disturbing because it throttled idealized images of small-town life and embraced the conflicts of its seedier underbelly, from incest and sexual assault to poverty, domestic violence and mental health issues. As creator Swery65 put it in his 2015 postmortem of the game,

"There are all these touchy issues in our game that most publishers -- or even game designers -- would just stay away from, but those things exist in real life, and I wanted to create a universe that realistically contained those elements. Whether that's a good or a bad thing is really a personal issue of the viewer/gamer, but from my perspective we can accept that these things exist in our world then we can accept them in a game; in the same fashion we see them in our real world, without implicitly condoning them.

"Realism is kind of hard to make, especially within a game," Suehiro continues. "People live their own lives, and they have their own perspective, but it's important to offer things that give your player something to think about even when they aren't playing your game. When I was a kid, I used to watch a lot of fantasy and science fiction, but as I grew up I matured, or learned that in many cases those are just lies; escapism. As we continue to make games, we should use fiction, of course, but I'd like to make games that are believable."

Suehiro’s comments are interesting in that horror games are meant to scare players, and yet they so often act as a power fantasy by ignoring the horrors of real life. While his motivations weren’t to necessarily scare his audience with the gritty details, they echo the comments of other designers, in that players need something they can identify with to become emotionally invested. In turn, this makes the story more effective.

10. And above all…accept that it can be hard to learn from other horror games

As director of Dead Secret Chris Pruett says in his interview with contributor Joel Couture, games comprise a cohesive experience that may not be easily dismantled for parts. Pruett made his game, about a journalist investigating a murder at a victim's home outside of town, after years of analyzing just about every horror title he could get his hands on, coming away with his own complex set of design values. His thought is that while it may be tempting to pick and choose from what worked for other games, like some kind of horror a la carte, the reality is a game is the sum of all its features interacting with one another and may not be as interesting or effective when isolated from those other parts.

"For example, is Resident Evil 4 better or worse because of its decision to forbid simultaneous movement and shooting? Clearly the developer felt so strongly about that decision that they chose to buck precedent. Would Resident Evil 4 be just as good with a different inventory management mechanic? A different control system? A different level design? It's hard to tell. The whole thing works so well that it's difficult to separate strands that might be repurposed from the whole.

"The best games transcend the sum of their parts and create something much more impactful. The trick is figuring out which, if any, of the decisions made in a good game might be applicable to another game."

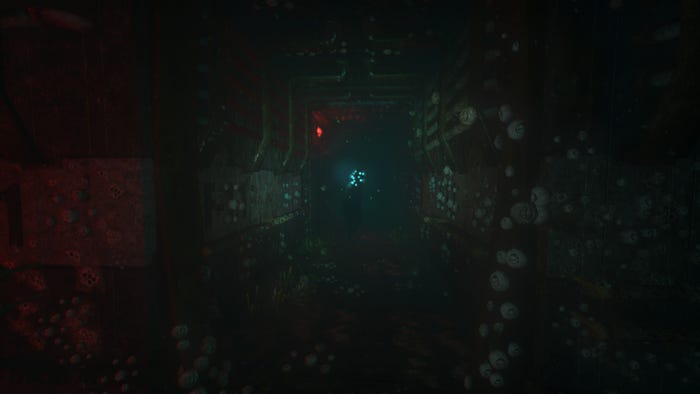

Image via SOMA Steam page.

GDC Vault

If video is more your thing, the GDC archives have some great (free!) materials.

SOMA - Crafting Existential Dread by Thomas Grip

Frictional Games' sci-fi horror game SOMA was created with a very specific purpose in mind: to explore the disturbing aspects of consciousness, the self and what it means to be human. Designing a game that could, through play, communicate this kind of thematic exploration posed a tremendous challenge. This talk covers the various design approaches the studio used and how they helped them achieve their goal.

Building Fear in Alien: Isolation by Alistair Hope

This talk covers how Creative Assembly overcame their own fear and uncertainty to create a new type of horror experience, revealing the journey from initial vision to their approach to utilizing the creature's senses to 're-Alien the Alien,' and how creating a visually and aurally immersive world was critical to the entire experience.

The Art of 'FAITH': Horror at 192x160 Pixels by Mason Smith

Can you create a compelling horror game experience using only basic graphics? Could a game that looks like Number Munchers (1988) feel like P.T. (2014)? A "retrograde" aesthetic was chosen for FAITH, inspired by the classic era of MS-DOS, Atari 2600, Apple II, and ZX Spectrum games. In this talk, indie game developer Mason Smith of Airdorf Games explains the decisions and principles that contributed.

Image via Left 4 Dead Steam page.

Community

Our community has also been a great source of horror game analysis over the years. Here are some of our favorites.

Building a Better Zombie by Christopher W. Totten Westwood College game design professor Totten takes a look at how zombies arose in popular culture, how they're used in other media, and explores how they have been used in games, and how they could be deployed even more effectively.

Scary Game Findings: A Study Of Horror Games And Their Players by Joel Windels Usability studio Vertical Slice measures player reactions to four Xbox 360 horror games to find out which game is the "scariest," how casual and core players react to the same games, and whether or not they are scared in the same way.

The Back Half of Horror Design by Josh Bycer The author discusses how most horror games tend to run out of steam before the end, and where things can be improved.

Opinion: How To Make a Scary Game by Mike Birkhead Former NetherRealm Studios designer Mike Birkhead examines what developers need to keep in mind while trying to create scary situations in their games.

Fight or Flight: The Neuroscience of Survival Horror by Maral Tajerian How exactly do horror games work on the brains of players? In this new feature, neuroscientist Maral Tajerian unpacks the mechanism behind the scares in Amnesia, Dead Space and Silent Hill and others.

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like