Why a recycling mechanic saved Terra Nil's climate cleanup design

Environmental strategy game Terra Nil needed to do what no other citybuilding game had done before to cross the finish line.

Free Lives' environmental strategy game Terra Nil launched last week to critical and commercial success—following a surprisingly strong amount of interest since the game was revealed in June 2021. This is after years of "climate crisis themed" games failing to get much of a footing in commercial game development.

What's driving the game's success? Well for one, players seem to be looking for hope that something can be done about the impact of climate change. Game director Sam Alfred told us in a chat early last month that since a demo for the game released in a 2021 Steam Next Fest event, there's been overwhelming interest from players about that topic.

As always, games about real-world topics only find an audience if they're actually engaging. And even though strategy simulation games have been a steadily growing genre in the last few years, that didn't make Terra Nil an "obvious" game to make. According to Alfred, its core design loop only came together after it tried something few citybuilders have ever tried before: letting players tear down everything they built.

Terra Nil's most innovative mechanic is recycling

To understand why Free Lives implemented a recycling mechanic, you have to go back to the game's origins. The game started as a game jam experiment (just like Free Lives' breakout game Broforce). Alfred took point on trying to make a climate-themed strategy game, and iterated on it over time to make something the whole company could get behind.

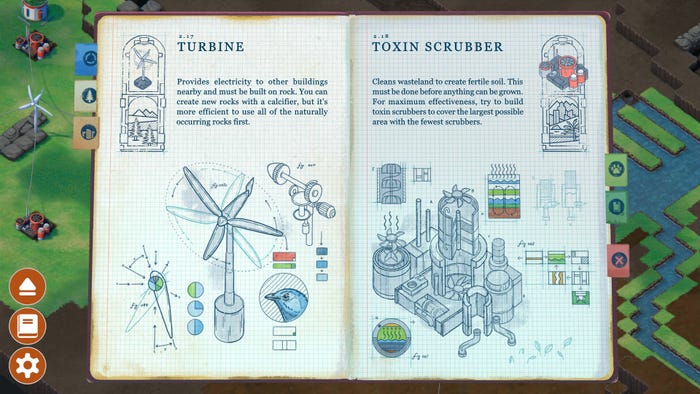

But the game jam prototype and following iterations had a fairly familiar strategy game loop. Players cleared out the toxic terrain of an Earth ruined by climate change, then built terraforming buildings to heal the land.

That was fun, but Alfred ran into a new problem: how should levels in Terra Nil actually end? All early attempts to build a satisfying end goal for the player ran into a repeating problem. "We just had too many buildings," he said. "So the epiphany [we had] was, 'okay, if we have too many buildings, we've got to take the buildings away.'"

Enter the recycling mechanic. After players begin to clean up the Earth and restore it to its natural state, now they get to "put away" the tools they used to do it. It's not the kind of mechanical flow you see in strategy or simulation games. Most such games end with players conquering their foes or surviving a natural disaster with a massive army or city still standing.

This mechanic lets the game's natural landscape—which Alfred said was inspired by the natural beauty of South Africa—"take center stage."

Alfred noted that this solution came while the game was still in pre-production, before more team members from Free Lives were brought on board. "I think if we got into full production [before the mechanic was designed] it wouldn't have necessarily looked that way," he said in reflection.

A Steam Next Fest demo boosted Free Lives' deal with Netflix

Terra Nil's success is also a key indicator of what Netflix's game subscription service could mean for the industry, but it wasn't an inevitability that the game would be a good fit for the still-growing service. Alfred pointed out that for developer Free Lives and publisher Devolver Digital, the game wasn't any of their initial "cup of tea." (The bulk of both companies' output is built on the back of very polished action games).

But once Netflix entered the equation, and a demo for the game was released in a Steam Next event, something clicked. "The game blew up way more than we or Devolver or Netflix or anybody thought it would," he recalled. Free Lives had signed the game with Devolver by that point, but this new burst of excitement shaped how the team cut a deal with Netflix. "It strengthened our negotiating position," he said.

The demo's success and Netflix's interest helped Free Lives built a bigger version of Terra Nil than it had originally anticipated. Alfred also said that Free Lives was able to stand its ground on the decision that Terra Nil couldn't be a Netflix exclusive. If Steam players were already excited for the game... how could they not release it on Steam?

So why go with Netflix (besides the money, obviously)? Alfred said that Free Lives wanted to getTerra Nil in front of a "more casual" audience. The climate crisis will impact players of all backgrounds, and being able to share a game meant to inspire hope for the future mattered a lot to the team.

"We're excited to see if maybe more casual players who aren't on PC, who play games on their phones—maybe we can reach way more people on Netflix than on Steam," Alfred enthusiastically said.

Terra Nil is definitely proof that games about the future of our climate have a place in the commercial video game world—and that mechanics built on hope (and maybe ones that work against capitalist extraction) offer a thriving possibility for making those games fun.

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like